Ferrovial

La ingeniería civil como arte: creatividad e innovación

Alignment

By Mary Peters

Innovative Infrastructure Solutions for Our Times

As one who admires and appreciates innovative infrastructure that improves quality of life in the United States and around the word, it is a pleasure to acknowledge the efforts of Ferrovial as represented through the pictures of José Manuel Ballester.

America once had the best road and transportation system in the world. Today the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report for 2019 ranks the United States 13th in the quality of overall infrastructure. Today the United States spends 2.3% of GDP on infrastructure, while China spends 9% on both domestic and foreign projects.

Investment in infrastructure as a percent of GDP fell by nearly 5% from 2003 to 2014. Spending on new or improved infrastructure as opposed to maintenance and operations fell nearly 25% during that same period according to the Congressional Budget Office. Over 54,000 U.S. bridges, 9% of total bridges, are considered structurally deficient, and 250 of the most heavily crossed structurally deficient bridges are on urban interstates. The average age of structurally deficient bridges is 67 years. We know that safe and efficient infrastructure is necessary for economic growth, creating jobs and saving lives. If the US is to remain viable in the global economy, we recognize that we must invest more to improve and expand our infrastructure.

What then has caused this significant underinvestment in infrastructure?

In terms of surface transportation, I believe that change began to occur as the Interstate Highway System was nearing completion in the late 1970s. When the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 passed Congress and was signed into law by President Eisenhower, the legislation increased the federal gas tax to three cents per gallon. This established the Highway Trust Fund, dedicating the revenue to building the interstate system. In the ensuing years, Congress increased the gas tax periodically to raise sufficient funds to cover the cost to complete the system. As the interstate system neared completion in the late 1970s, many thought the tax should devolve to the states to maintain, operate, and improve the system.

These discussions came to a head in the early 1980s. President Reagan opposed further increases to the federal gas tax and supported devolution to the states. Most in Congress disagreed; they overrode his veto and raised the tax by 5 cents per gallon. By 1993 the tax was 14 cents per gallon. Congress increased the tax by an additional 4.3 cents per gallon, but instead of dedicating the full tax to highways and transit, they designated the additional funds to U.S. budget deficit reduction, plus one cent for leaking underground storage tanks. Some say this broke the “trust” in the Highway Trust Fund, and it would be the last increase in the fuel tax to date.

In the ensuing years, committee chairs and other powerful members of Congress diverted funds to favorite (pet) projects often called “earmarks,” in their own state or district rather than to the infrastructure system based on needs. After a bill reauthorizing the fund passed in 2005, containing a record number of earmarks, including a so-called “bridge to nowhere” in Alaska, Congress swore off earmarks in response to public criticism of the practice. Since that time, members of Congress and presidents alike have been unwilling to propose, and the public unwilling to support, an increase in the fuel tax.

A few of us at the time saw that an almost complete dependence on public funds to meet U.S. infrastructure needs was no longer prudent nor possible. We looked to countries like Spain and Australia and noted the success they were having in attracting private funds to meet those needs. Fortunately, companies like Ferrovial were coming to the US and willing to invest private funds in infrastructure and help us understand the value of private investment.

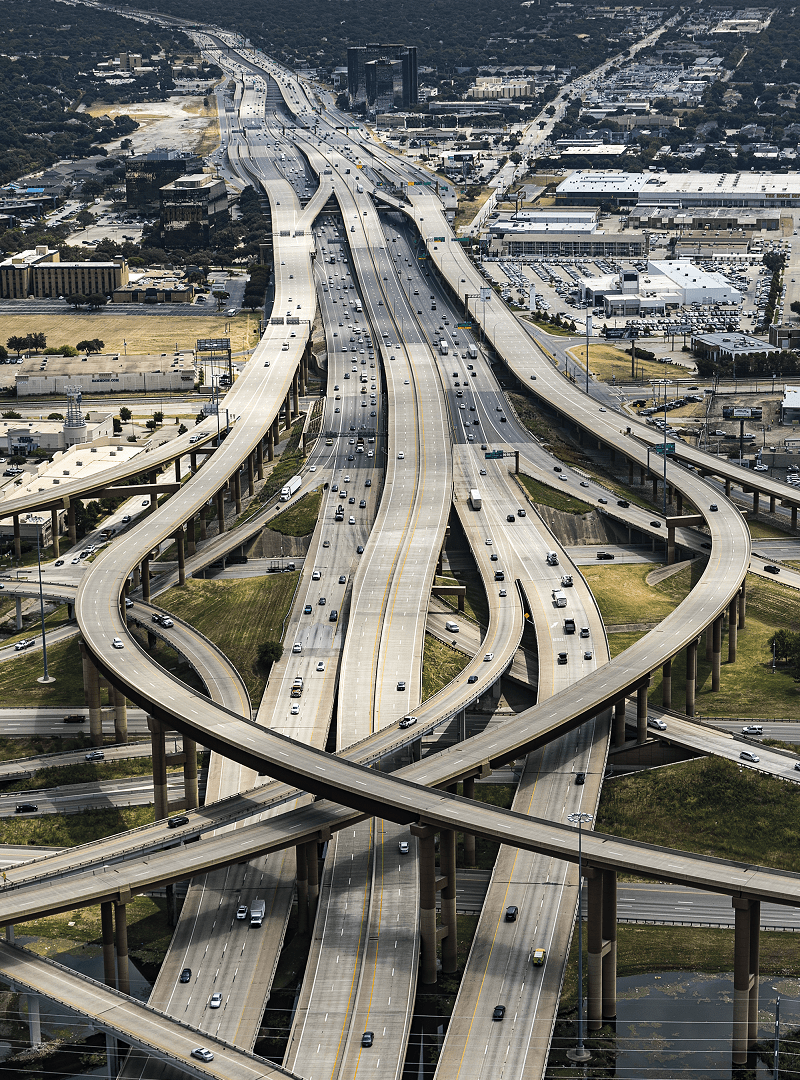

This knowledge allowed us to work with the states and Congress to create and expand tools like the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) and Private Activity Bonds (PABs), which have helped encourage private investment. Several states including Texas and Virginia passed legislation creating public–private partnerships, or P3, to invest in critical infrastructure projects. These investments have passed the test of time, with very successful projects continuing to operate today in the areas of Dallas– Forth Worth, TX, northern Virginia–Washington, DC and Charlotte, North Carolina. First as the head of the Arizona Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administrator, and later U.S. Secretary of Transportation, I saw the value proposition in these partnerships.

P3s not only brought additional funds, they helped us use an asset investment discipline to choose the right project—those that met high demand and would generate revenue to repay the private investment. Further, these projects were built with a lifecycle cost approach, and we found that the cost to maintain the projects was significantly lower than the design-bid-build method.

Recognizing the value of private investment by working with Cintra and others has been important and will be even more critical in the future. With the buying power of the flat fuel tax yielding less revenue, coupled with better fuel economy in the vehicle fleet, and reductions in the annual vehicle miles traveled, the Highway Trust Fund faced insolvency in the fall of 2008. As US Secretary of Transportation at the time, I had to notify the president, Congress and the states that they would be receiving less funding than legislation had promised.

Today we are facing economic uncertainties—the kind that perhaps will have similar or perhaps greater impacts than what we experienced in 2008–2009. The U.S. budget is facing even greater challenges in non-defense discretionary spending. A worldwide pandemic coupled with record levels of unemployment is affecting our economy in ways whose depth we do not yet know. But we do know that safe and efficient infrastructure is necessary for coming out of the recession and once again seeing economic growth.

We do know that expanding and improving our infrastructure will create jobs and save lives. We do know that we cannot get there from 13th place. On June 8, 2020, Forbes published an article from the World Economic Forum titled “How Transportation Innovation Can Support COVID-19 Recovery.” The article states, “As communities across the globe grapple with pandemic responses, the value of public–private partnerships and technology integration has never been more clear.” I could not agree more!

Mary Peters, Former U.S. Secretary of Transportation